In an 1852 letter to Joseph Weydemeyer, Karl Marx wrote:

‘No credit is due to me for discovering the existence of classes in modern society or the struggle between them, [rather] 1) that the existence of classes is only bound up with particular historical phases in the development of production, 2) that the class struggle necessarily leads to the dictatorship of the proletariat, 3) that this dictatorship itself only constitutes the transition to the abolition of all classes and to a classless society.’(1)

Throughout his writings, Karl Marx offered not only a critique of capitalism, but also what is essentially a declaration of our final societal condition: communism. He is not so much an advocate for communism and what he sees as its qualities, rather he explores the conditions of political and economic history, and the ostracised human desires that have now formed a communal desire for it, thus leaving its implementation supposedly inevitable. This quote, in brief, summarises his view of this communal integration of society – a destruction of the class system as inescapable. These claims are derived through an analysis of inter-societal relations, and the palpable observation of alienation caused by the economic subsistence of the proletariate. He critiques the view of bourgeois economists who, he argues, base their explanations on a faulty understanding of human nature – Marx says these factors are not natural, but instead, societal. To think that the individual thinks, and behaves, equally to all others is a mistake; these behaviours are created by the all-encapsulating system that has obligated them to act this certain way. There are no doubt elements of real truth to all of Marx’s claims; the questions boil down to if, when, and how this transition takes place. I believe Stardew Valley may provide some direction.

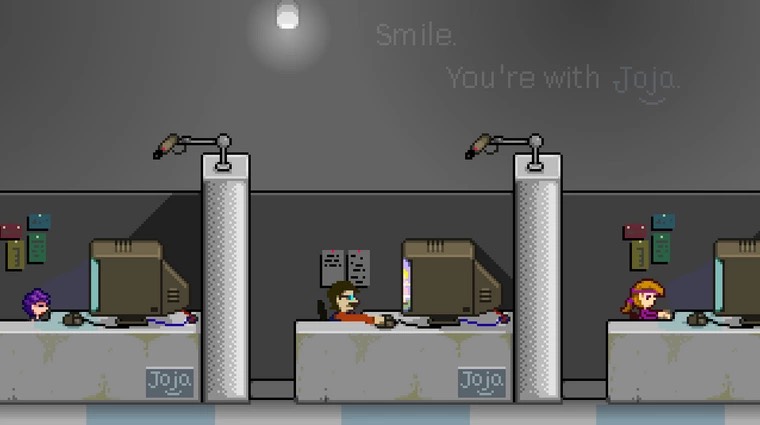

Released in early 2016, Stardew Valley is a farm-life RPG built off the premise of a very similar notion to what Marx advocates: you are a disillusioned young Joja–Corp worker facing the brunt of modern capitalism, doing machine-work in a socially-atomised space for an entity with zero concern for your well-being. All the while, being fed meaningless slogans like ‘Smile’, ‘Thrive’, ‘You’re with Joja’ and having your work surveilled by desk-cameras. Interestingly, the game is not set in a futuristic land far away – the initial setting is not dissimilar to what you may find as an employee of a large 21st century firm. And the success of Stardew Valley is no doubt attached to our real-life desires; on some level, we play Fifa because we enjoy football, we play Call of Duty because we enjoy shooting things, and we play Candy Crush because we enjoy solving puzzles. In the case of Stardew Valley, I believe there is something deeper; developing the courage to escape from the golden handcuffs of Joja and move away from the comfortable grey pod to the high-contrast, beautiful world of Stardew Valley bears a shocking resemblance to the derived demand that many have in wider society. However, instead of abolishing said social classes, we are escaping them.

In the medium-specific level of Stardew Valley’s game mechanics, we find a plethora of mechanics that serve as indicators to what Marx foresaw. This isn’t limited to the simple joys of fishing or farming – which are obviously not possible in our concrete jungles –, but includes the development and maintenance of friendships and social order within a tight-knit community. Over the past twenty months lockdown and social distancing mandates (2) have catalysed the already-proceeding disaggregation of our closer societies. City-work now is almost always part-virtual, office capacity has dramatically fallen, and companies like Zoom have skyrocketed. All the while, surveillance has persisted, and further rules have been developed: wear a mask, get a vaccine, social distance. For better or for worse (or for necessary), the widening scope and increasing quantity of rules are an omnipresent reminder of the capitalist power structure we have found ourselves in.

I am reminded of Peter Thiel’s implied explanation for the propagation of our capitalist system in Zero to One, wherein for the older generations ‘things just got better year after year … they followed the system, and their quality of life improved along with it.’ (3) This is no longer the case – entry-level jobs even out of the best institutions no-longer provide the means to support a family of four, and one cannot finance their college education by selling encyclopaedias. With significant concerns about national debt, climate change and the more-recent inflation spikes (4), the capitalist structures that be have allowed our preceding generations to take loans from their young, which the latter will have to pay off. And the only consent required was their own.

With these circumstances at hand, one important question is: why bother? This is a question that we’re posed, and one to which we have our answer handed to us, in the opening cutscene of Stardew Valley: Why bother spending my best years grinding away for Joja-Corp? Perhaps the kind of life led tending to a farm surrounded by a valuable community within which I can find my wife or husband, and sustain myself and my family would cultivate a more fulfilling life? Ironically, this bears resemblance to the original American Dream: living off the fatta the lan’ like George and Lennie in Of Mice and Men. (5) And yet, per Marx, the condition we find ourselves in and the human desires that have been ostracised have now resulted in a communal desire for systems which operate on a near-opposite premise to that from which America was built. How and whether these new systems actualise themselves is a key question here, however it seems quite certain that modern American giga-corporations, despite their extraordinarily-funded PR campaigns and HR departments, have no intention of leading the charge. Instead, there may be no charge; rather baby-steps easing us in that direction. Stardew Valley does not force us anywhere, but perhaps it serves as a stepping stone to subliminally generate questions about the state we, and society at large, are in – and the solutions.

Citations

1 Marx, Karl, Friedrich Engels, and Robert C. Tucker. The Marx-Engels Reader. New York: Norton, 1972.

2 Gupta, S., Simon, K., & Wing, C. (2020). Mandated and voluntary social distancing during the COVID-19 epidemic: A Review. https://doi.org/10.3386/w28139

3 Thiel, P., & Masters, B. (2015). Zero to one notes on startups, or how to build the future. Virgin Books.

4 Smith, C. (2022, January 28). US inflation gauges expected to show sustained rising pressure. Subscribe to read | Financial Times. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.ft.com/content/8ca4b68d-9df4-45a3-ae7b-09bfd9cc58b7

5 Steinbeck, J., & Steinbeck, J. (1986). Of mice and men. Penguin.