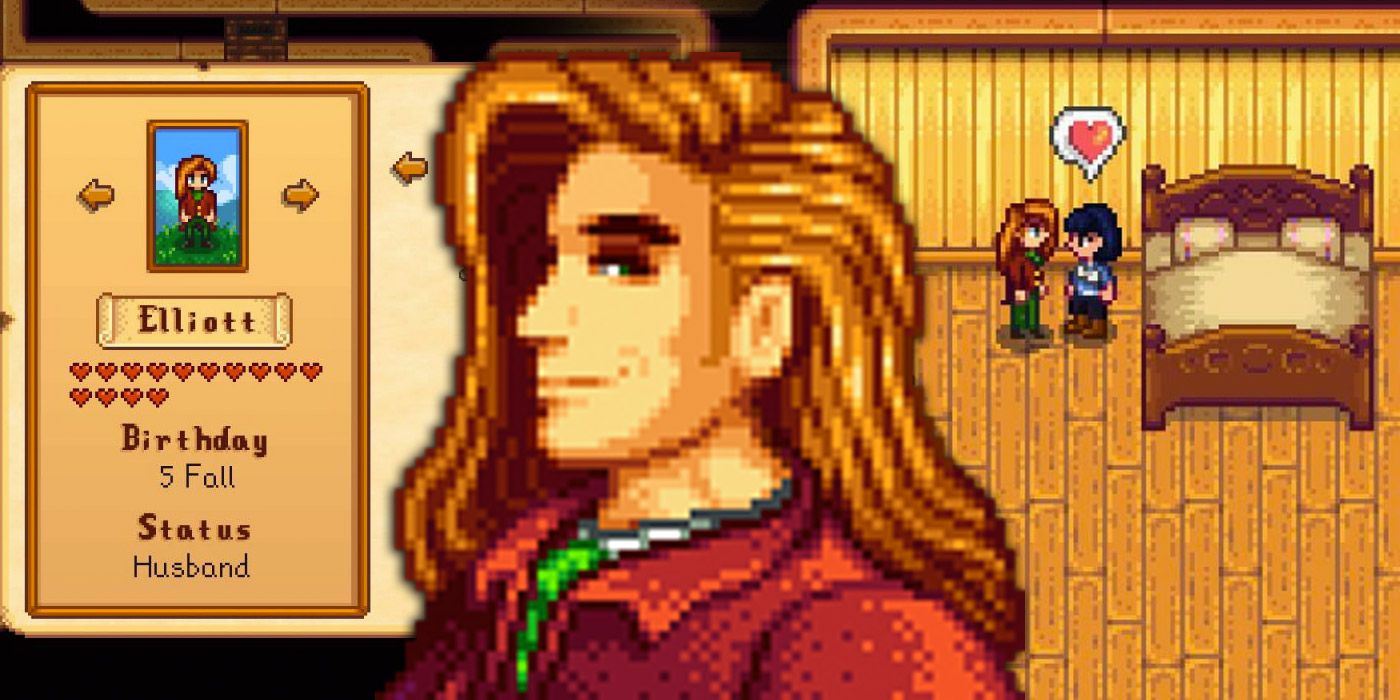

Scarcity is a simple term used within economic theory to refer to an instance where the supply for a good is less than the demand for it; thus, it is a common human reaction to want what seems rare and limited. And in my eyes there is no better way to refer to the man made of shimmering ginger locks—or as those who are less romantic would refer to him as Elliot—than that of a rare jewel just waiting to be snatched. For in my controlled single player world of Stardew Valley, Elliot is the perfect commodity in which I can leisurely buy at my own pace; there’s no incentive to pre-order him as the game disallows any other demand for him except for myself. However, enter the world of online multiplayer and your once perfect man is acting as a promiscuous jezebel that just loves all the attention he receives from the other human players; thus, spurring not only my severe objectification of Elliot that framed him as a prize but also a competitive edge within me to gain superiority over the other players in my farm in any little way possible.

Elliot at the in-game Luau event.

For the addition of another player in the realm of Stardew Valley seems on paper the ideal way to collaborate and grow a farm together. The addition of extra hands and resource gatherers theoretically makes farm growing go exponentially faster; however, there exists these somewhat hidden motivators within the game that breed competition and reflect a more neoliberalist approach to farm building that has one look out for themselves. In our fight for Elliot, we realized that villagers are the only one true object that possesses a sort of scarcity about them. In a game where the resources of the world around you can never be permanently depleted, villagers are commodified in order to create some sort of economic scarcity within the market. I believe that our motivation behind romancing the same person was the competition itself and not our actual love for Elliot. The joy of the reward is derived from the expense of the other player; thus, we are still able to be aggressive and competitive in a game where direct combat is not possible. However, even if players are to agree upon different love interests, there are still passive aggressions players can commit embedded within the game. In my personal game of Stardew Valley multiplayer, I always rush out of bed in the morning when there is a crop harvest in order to be the one to pick them. On paper, I was able to tell my farming partner that I will do this laboring task as they do something else as we equitably share the profits; however, there is a seed of competition within me when doing this as the farming skill in the game is level up through the hidden value of harvesting crops. I could have my partner plant, water, and fertilize all the crops in the yard; however, if I am the sole one to harvest them after they are ripe, I get all the benefits.

So while Stardew Valley does try and incentivize a multiplayer experience that is equitable and fair—we can see this with the option to turn off shared wealth, allow larger land plots for cabins, etc.—it can never escape these small glimpses of inequality that the player can capitalize on to boost their own capital. For just when I thought the nature of the game was rooted within these small back stabbings, I experienced the MADD center local-coop session in which we all played together in the same room. On this file, I acted as the complete opposite of my normal usual money hoarding self and attempted to just enjoy the game for the small allotted time we had available. This had me brining parsnips and beer to my other classmates, collecting and gifting wood to those who wanted to build the bridge for pretty seashells, and finally spending 1000g on a Christmas tree that I put in the center of Pelican Town that we all rejoiced around (this very unseasonal for Spring 6, I would like to note). I had finally escaped this capitalist need to play this game for profit and individualized improvement. An escape with upon reflection I believe to be a result of wishing to be less proceduralist and more play centric.

For before attending the Stardew Valley co-op session, I had just read Miguel Sicart’s “Against Proceduralism” essay, and as someone who often and maybe too quickly adapts the theory of academic arguments I read, I decided to go in with the this newfound approach to being player centric. For I wanted to escape this idea of being a simple procedural executioner of rules that Sicart writes about as in proceduralism, “players are important, but only as activators of the process that sets the meanings contained in the game in motion.” For by purposefully avoiding what I believed the game incentivized me to do with my time and money, I decided to create meaning myself with abnormal acts. Granted that the nice thing about the session is that it was in a contained time frame in which I never had to worry about the consequences of my actions as I would never play this farm again after two hours, I let myself be free and my main goal was just trying to make the people around me laugh through wacky antics like the Christmas tree or playing hangman in the chat feature. I feel as if there is a certain rigidity and cruelty within a proceduralist mindset that sets us on a path to be as successful as possible because all we seek is to game the rules as much as possible for our own advantage. But when a play centric mindset is implemented, I found I was not only having a better experience but also directed care back into the people around me, freeing me from the competitive urge to be better or “win”.

Works Cited:

Sicart, Miguel. “Against Proceduralism” Game Studies, The International Journal of Computer Game Research. December, 2011.